November 10, 2021

By Daniel H. Gillison

Every year on Veterans Day, we celebrate the brave individuals who have served our country through the armed forces. Here at NAMI, we recognize that even after leaving a physical battlefield, many in the military community continue to fight mental and emotional battles.

Research suggests that 11–20% of veterans experience PTSD in a given year — significantly higher than past-year estimates for the general population at less than 4%. Suicide rates of military service members and veterans are also at an all-time high, with deaths by suicide having increased by 25% during 2020.

As someone who grew up in a military family — both my dad and brother served as paratroopers in the U.S. Army — the conversation about veterans’ mental health is personal and critically important to me. It’s also timely, as the 9/11 era has officially ended with the withdrawal of our remaining troops from Afghanistan just two months ago.

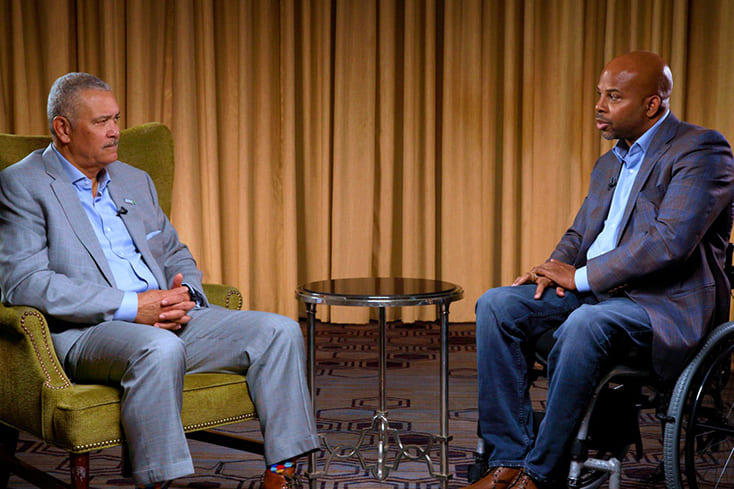

Today, I wanted to use my platform to talk with Sherman Gillums, Jr., our chief strategy officer here at NAMI, who served in the U.S. Marines for 12 years and has been an advocate for veterans’ health ever since.

Check out our conversation below (the dialogue has been edited for clarity and length):

A Lifelong Sacrifice

Gillison: Sherman, I want to start out by first of all thanking you for your service. As an opening question, I’d like to ask you, what does it mean to be a veteran in today’s military?

Gillums: When 9/11 happened, all of us were shocked by what we saw. At the time, it felt good to answer the call to serve, and to be able to do something at a time when a lot of us felt helpless. Twenty years later, the war has officially come to an end. But in a way, a war never really ends for those who have to live with the consequences.

In many ways, being a veteran means not only honoring service but also being there after service. There is a lifetime commitment and obligation as a veteran. The mental and physical burdens we carry is a lifelong cost.

&np;

bs

On the Home Front

Gillison: A lot has happened recently with the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the loss of Secretary of State Colin Powell and, of course, COVID-19. How does our military family feel right now? Is there a sense of loss? Hope?

Gillums: The battlefront gets a lot of attention. But the homefront is where a lot of the unseen consequences happen.

The losses veterans experience aren’t just physical ones, like missing limbs or broken bodies; there is an emotional loss as well. There is also a cost to families who are impacted. There is a cost to children who grow up with a parent who hasn’t adjusted well to returning to the civilian sphere. There is a cost to their children’s children as trauma is passed down.

Hope is born from seeing previous generations make it through and heal.

My grandfather served in Korea, and he came back and raised three daughters and did very well. I was in the Marines; my wife was in the U.S. Army and served in Afghanistan for 18 months; and now my daughter is at the Naval Academy. We’ve been really intentional about figuring out what it means to heal as a family.

My work here at NAMI informs a lot of the advice I give to other people, but it also informs how I look at our responsibility to self-care and heal ourselves.

Suicide Prevention

Gillison: This past summer, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin expressed deep concern about growing suicide rates in the military community. It felt like a big step to hear him talk about it. In your opinion, what else needs to be done to address military suicide?

Gillums: It was very important for top leadership to say that. Military culture is the antithesis of recognizing pain, admitting to even perceptions of something that is considered “weakness” and asking for help. So when the defense secretary said that, he opened up a space for people in the military to also be human.

A lot of people come into the military in pain. Suicide rates aren’t just a reflection of what happens during service. By the time they suffer an injury or end their career, those experiences can revisit them on top of any trauma they went through during deployment.

Many of our veterans experience a lost sense of purpose when they leave the military. To help combat suicide and provide hope, we need to remind them that the military is not their whole identity, and they have many reasons to live outside of their service.

Finding Hope

Gillison: Sherman, thank you so much for sharing your thoughts and experiences with us today. I wanted to conclude by asking you: Do you have a message for other veterans you would like to share?

Gillums: To any veteran hearing this, you’ve been asked to be strong for a long time — stronger than most people in most professions. But there's a chance to find strength in broken places too. It’s about understanding what you are going through and finding meaning.

And there is meaning in the example you set, especially for younger people. You were an example in uniform. Now it’s time to be an example in life.

I encourage veterans to see finding hope and purpose in their own life as a way to continue serving their country. If we can make that the custom for all veterans, we will save so many more lives.

Gillison: Thank you, Sherman.

If you are a veteran, or if you know a veteran who is struggling with their mental health, there are resources available to you. You can visit homefrontresources.nami.org or see the resources below for more information.

Veteran Mental Health Resources:

- Veterans & Active Duty Mental Health Concerns – NAMI

- NAMI Homefront Mental Health Resources (free mental health wellness tips and advice) – NAMI

- Veterans Crisis Line

- Department of Defense Helpline – Military OneSource

- Veteran Health Care – Tricare, Defense Health Agency

- Veteran Mental Health Resources – U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

- National Resource Directory

Daniel H. Gillison, Jr. is the chief executive officer of NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness). Prior to his work at NAMI, he served as executive director of the American Psychiatric Association Foundation (APAF) in addition to several other leadership roles at various large corporations such as Xerox, Nextel, and Sprint. He is passionate about making inclusive, culturally competent mental health resources available to all people, spending time with his family, and of course playing tennis. You can follow him on Twitter at @DanGillison.

Daniel H. Gillison, Jr. is the chief executive officer of NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness). Prior to his work at NAMI, he served as executive director of the American Psychiatric Association Foundation (APAF) in addition to several other leadership roles at various large corporations such as Xerox, Nextel, and Sprint. He is passionate about making inclusive, culturally competent mental health resources available to all people, spending time with his family, and of course playing tennis. You can follow him on Twitter at @DanGillison.

Submit To The NAMI Blog

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices.

LEARN MORE