April 27, 2022

By Casey Clabough

As those of us who live with the diagnosis know, schizophrenia is a difficult condition to relate to. Most people can sympathize with someone who is suffering from an evident physical injury, such as a broken leg. They can also understand the plight of someone with a less visible illness, like cancer. Perhaps they haven’t experienced those particular medical issues, but they can imagine the physical pain and conceptualize the fear.

On the other hand, a serious mental illness like schizophrenia can be more difficult to imagine, as it affects one’s ability to interpret reality, often without any apparent physical symptoms. Much of the general population will never experience this, nor are they able to imagine battling their own minds in this way.

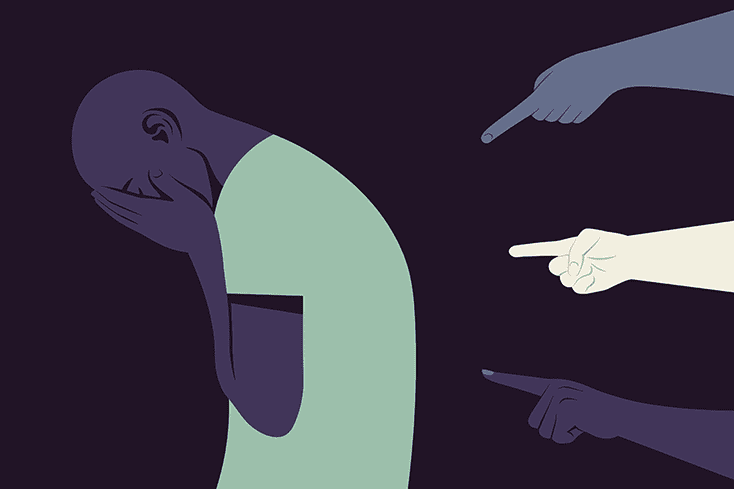

Due to our possible misinterpretations of reality, those of us with schizophrenia may say and do things that seem bizarre to others, further alienating us from other people — even people who wish to help or understand us. For this reason, we suffer an onslaught of stigmatizing assumptions, labeling us “crazy” or “insane” — language with negative connotations that is never used to describe someone healing from a physical problem.

The cycle of social stigma and misinformation compounds the already-challenging experience of managing a mental health condition.

Stigma Perpetuates Fear

Awareness of the lived experience of schizophrenia is lacking; a relatively small percentage of Americans feel as if they are familiar with schizophrenia, and many who have heard of the condition are fearful of encountering people with schizophrenia at work or in their personal lives — even those who are undergoing treatment.

This stigma is exacerbated by negative press coverage. Often, when someone with schizophrenia appears in the media, it is usually in relation to a violent incident — even though, statistically, people with schizophrenia are less likely to commit violent acts than those who do not have the condition. In fact, people with schizophrenia are more likely to be victims of violence than are members of the general population.

With media representations painting a different picture, how is someone who wishes to understand able to set aside the condition’s negative social connotations and lend support? If people continue to see those living with this condition as inherently “crazy” rather than ill, how will we move forward?

Stigma “Others” Us

In addition to combatting the misinformation and misleading representations of schizophrenia, people with the condition often struggle to self-advocate, as they often feel different from the average person. For many of us with schizophrenia, communicating with and persuading a large audience (in hopes of educating about schizophrenia and our lived experience) is difficult and even frightening.

Those managing noticeable symptoms fear being seen as “strange,” and we become acutely aware of the ways in which they lack an ability to relate to other people. It often feels as though the mental and emotional functions that allow humans to connect have been set askew in some way.

Stigma Encourages Isolation

The result of widespread stigma is not simply an unfortunate social experience for those with schizophrenia — it is a life-threatening challenge. The life expectancy of someone with schizophrenia is roughly two decades shorter than that of the general population, arguably due to the prevalence of suicide among people with the condition (specifically among those who do not seek help, fearing stigma and discrimination). Oftentimes, those who die by suicide are considered “high-functioning,” as they are aware that they are sick and can comprehend the extent of their social isolation and perceived dysfunction.

But this does not have to be the reality. If we can commit to educating ourselves on the condition, promoting accurate and nuanced representations of schizophrenia and prioritizing advocacy, we may see more favorable times to come.

Casey Clabough, who lives with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, is an author and editor. This blog post is an edited excerpt from his manuscript, “Writing Schizophrenia; A Memoir of Madness.”

Submit To The NAMI Blog

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices.

LEARN MORE