July 12, 2023

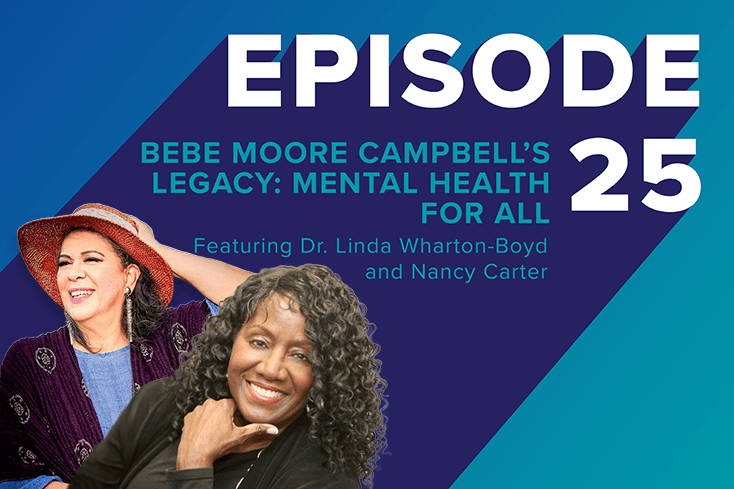

In this episode of NAMI’s podcast, NAMI CEO Daniel H. Gillison Jr. speaks with friends of Bebe Moore Campbell, Dr. Linda Wharton-Boyd and Nancy Carter about Bebe’s impact and how we can all play a role in keeping her legacy alive.

You can find additional episodes of this NAMI podcast and others at nami.org/podcast.

We hope this podcast encourages you, inspires you, helps you and brings you further into the collective to know: you are not alone.

Episodes will air every other Wednesday and will be available on most major directories and apps.

Episode Audio:

Episode Video:

Featured Guest:

Dr. Linda Wharton-Boyd

Dr. Linda Wharton-Boyd was a longtime friend of Bebe Moore Campbell who conceptualized the idea of a national minority mental health month. After Bebe’s passing, she worked with others to pass legislation that officially designated July as Bebe Moore Campbell National Minority Mental Health Month in Bebe’s honor. Dr. Wharton-Boyd continues to keep Bebe’s legacy alive through her work with the Bebe Moore Campbell Minority Mental Health task force and the “Erase the Stigma, Not Her Name” campaign.

Nancy Carter

Nancy Carter co-founded NAMI Urban LA (formerly NAMI Inglewood) with Bebe Moore Campbell and served as a past board member of NAMI National. She is a fierce advocate, passionate peer and loving family member. As one of Bebe Moore’s late friends, she is passionate about keeping Bebe’s legacy of mental health for all alive today and always

Share on Social Media:

Episode Transcript:

[0:00]

[background music]

Linda

Wharton‑Boyd: [0:01] One of the things that Bebe was very clear on,

and that was that if we could erase the stigma of mental illness in our

communities, our people would be more ready to get help. We’re going to leave

this black woman’s name alive and moving, because this movement that she

started is for real.

Nancy

Carter: [0:17] Bebe came into my life in 1999 for a reason, she stayed for

a season, and she’s been in my heart for a lifetime. She gave all of us that

energy and that impetus to say we can fight back.

Dan

Gillison: [0:31] Welcome to Hope Starts With Us, a podcast by NAMI, the

National Alliance on Mental Illness. I’m your host, Daniel H. Gillison Jr, NAMI

CEO. We started this podcast because we believe that hope starts with us.

[0:46]

Hope starts with us talking about mental health. Hope starts with us making

information accessible. Hope starts with us providing resources and practical

advice. Hope starts with us sharing our stories. Hope starts with us breaking

the stigma.

[1:02]

If you or a loved one is struggling with a mental health condition and have

been looking for hope, we made this podcast for you. Hope starts with all of

us. Hope is a collective. We hope that each episode with each conversation

brings you into that collective to know you are not alone.

[1:20]

Today, I’m joined by longtime friends of Bebe Moore Campbell, Nancy Carter, and

Dr. Linda Wharton Boyd, in honor of BB Moore Campbell National Minority Mental

Health Awareness Month.

[1:32]

We are so thrilled to be able to share about Bebe’s legacy and how we are all

continuing to carry the work she started forward today. Personally, I met Bebe

way before I ever thought I would ever be CEO at NAMI or even working in the

mental health space. I had no idea that she was an acclaimed writer, a national

speaker, and the mom of a Hollywood actor.

[1:54]

I didn’t know about her involvement with NAMI, or about all the struggles she

faced trying to find resources for her daughter living with bipolar disorder. I

just knew she was a college friend of one of my friends and former colleagues

at Xerox.

[2:08]

One night when Bebe was in DC working with Congress, my friend hosted a dinner

and I was fortunate enough to meet her. She created a lasting impact on me over

15 years later, and I’m proud to be working in this space, hoping that I’m

truly continuing the work she started.

[2:23]

There’s so much that can be said about Bebe. Can you all share more about Bebe?

Who Bebe was to you and how you met her, and some things people may not know

about her? Nancy? Linda?

Nancy:

[2:37] I’d like to throw it to Linda and just make a slight correction, Dan. I

wish that I had been Bebe’s longtime friend. We had a very short relationship.

There’s an old saying that people come into your life for a reason, a season,

or a lifetime.

[2:54]

Bebe came into my life in 1999 for a reason that we all know, she stayed for a

season, and she’s been in my heart for a lifetime. We actually only knew each

other from ’99 until she passed. Linda was her longtime friend forever and

ever. Linda, I think you should take this ball and roll with it first.

Linda:

[3:16] Sure. I’d love to. Listen, Bebe and I were classmates at the University

of Pittsburgh.

Nancy:

[3:22] I know.

Linda:

[3:22] She came from Philadelphia and I came from Baltimore. Our intersection

was at the university. You had two urban girls coming together at the

University of Pittsburgh. We worked together. We joined the Black Action

Society.

[3:38]

Bebe started an organization ‑‑ I always like to tell people ‑‑

called Black Women for Black Men. She always about connecting. She was always ‑‑

even on during the campus ‑‑ she was always connecting us. She came

with a serious mind to write and to improve her writing.

[4:01]

She studied under several well‑known authors that taught at the

University of Pittsburgh. We stayed together all these years. It just goes back

to 19 dot, dot, dot. Unless you know how old I’m. Goes back to 1969. She was

ahead of me, but we came together.

[4:25]

The intersection was at the University of Pittsburgh, and we just became

friends and remained friends throughout the years. She supported my family, I

supported her family. We knew her daughter. With that through her first

marriage and then her second marriage with Ellis Gordon.

[4:41]

Her beautiful granddaughter, Alicia, and her mom, oh my God, her mom was the

center of her life. She was very much a part of our lives as well. Knowing Bebe

was like knowing, everybody say your BFF, she was a BFF. She’s a BFFF, a friend

forever and forever and forever.

[5:02]

We find it not robbery to share her passion with others, share her advocacy and

mental health, and when you read her writings, she was able to delve deep to

the soul of a person. That was also indicative of who she was. She came to you

full steam ahead. You got the full flavor of Bebe Moore Campbell when you met

her.

Dan:

[5:30] That’s so true in terms of just the impact that she had and her writing.

I brought with me something I wanted to show everyone real quickly and this is

one of her books, "72 Hour Hold." It’d be one of Bebe’s great books.

Here is a picture of Bebe on the back.

Linda:

[5:51] There she is.

Dan:

[5:52] Important for me is that in me getting this Bebe signed this for me on

the 30th of June, which is very soon, if you will, of 2005. If you think about

where we are in 2023, this is incredible to talk about this. Bebe made a huge

impact for so many underserved communities, especially communities of color.

[6:19]

She stood for those who were miscounted, misunderstood. marginalized,

undervalued, underrepresented. When there were no resources for her

predominantly Black and brown community, she went to fluent White

neighborhoods, found resources, and brought them back. She started out by

advocating for her daughter because there is truly no greater advocate than a

mom.

[6:41]

What started out as advocacy for one turned into advocacy for so many. Can you

both talk more about what Bebe did to create impact and awareness about mental

health conditions in underserved communities, especially communities of color,

and why was that so important?

Nancy:

[6:59] I can speak to that, Dan, because that was the focus of our relationship

in the years that we spent together. As a little background, Bebe and I met in

a strange way. I wrote an article for one of the NAMI magazines. It was called

From a Whisper to a Song, and the whisper came in a phone call to me on my

answering machine.

[7:25]

I came home one night in 1999. My son was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in

1994. He was also an actor up and coming. Bebe and I shared a best friend. I

was in one ear. She was in the other ear. Finally, the friend said, "You

two need to talk," but Bebe had celebrity, I did not.

[7:48]

She did not want to talk to a stranger and certainly didn’t want to put her

business in the street and was very clear about that. The phone call came

anyway, and I heard the voice. As soon as I heard it, I knew why she was

calling. I thought, "Oh, my God. This woman that I admired so much. I had

gone to book signings and thought, ‘Oh, Lord.’"

[8:10]

Then, in that moment, I realized, "Oh, my God. I think we’re in the same

club." I picked up the phone, I called. Again, reluctance on her part. We

finally figured we needed to meet. She said, "Do you go to church?" I

said, "Yeah." She said, "Why don’t we meet at church?" I

thought to myself, yep, because she’s not going to invite me to her house yet.

[laughs] She doesn’t know me.

[8:39]

We met in church, OC Smith City of Angels, and five minutes into the service, a

hand reached out to me and I reached out to her. For the rest of the service,

we were holding on to each other for dear life, tears streaming down our faces.

When it was over, we hugged and she said, "Girl, do you want to come over?"

I said, "Yeah."

[9:01]

Linda, that’s when I first heard about you when we got to her house. It was she

and her mom, and we were sitting around the kitchen and talking about the fact

that it couldn’t just be the two of us struggling like this. I said, "Well,

I had heard this through school, I went to Howard, a few people there, but

nobody’s talking."

[9:21]

Of course, your friend who would start things said, "We need to find more

people. We need to have a group. We need to do something about this."

[laughs] I cracked up, and I said, "OK, yeah. Let’s try it." Again,

she wanted to do it, but she was reluctant for people to know. She said,

"I don’t want to do it at my house." I said, "I don’t care. We

can do it at my house."

[9:47]

Literally, in the living room where I’m sitting right now, we started what

would become NAMI Inglewood, NAMI Urban Los Angeles. There were five of us to

begin with, and we were a mother’s prayer group. At that point, all we knew to

do was pray.

[10:06]

We knew we had been dropped into the middle of the ocean, and the tsunami had

come and swallowed all of us, and where were we going to go from there? Our

kids were in trouble. I told everybody, and we all agreed from the moment that

the diagnosis came in and the breaks happen, you start calling on the Lord in

ways you never thought you would call on Him.

[10:32]

We said, "We pray." We prayed at the beginning of every meeting, and

we prayed at the end of every meeting. In the course of that, Dan, Bebe found

NAMI. She and her mother went and took the 12‑week Family‑to‑Family

class and came back and said, "We really should do this. We should all

take the class," which we did.

[10:53]

At the end of it, the lovely instructor, who, as an aside, I will tell you,

called Bebe Baybay for the first six classes until she heard her on NPR and

realized, "Oh, it was Bebe Moore Campbell, New York Times Bestselling

Author." We had a laugh about that for quite a while.

[11:16]

The long and the short of it is, Baybay and all of us were invited to take the teacher

training, which we did. All of us had grown up with that old trope of whom much

is given, much is expected. At the end of it, we knew we had to teach these

classes and pay it forward.

[11:37]

The question was, where would we do it? I live in Santa Monica on the Westside

in California, and I was content to stay right here. Bebe said, "No."

We needed to do it in the Black community. We needed to do it over where she

lived.

[11:52]

I reluctantly said, "OK, I guess I’m driving to Leimert Park."

[laughs] We ended up starting our first class in, it was 2002, and shortly

after, I said, "If we’re going to do this, we need to have our own

affiliate." There was a lot of pushback, "Do we really want to do

this? Do we not want to do this?"

[12:16]

Bebe arranged for us to go to group therapy, because at that point, we all knew

each other rather well, and they knew that I also had a bipolar diagnosis. The

thought was, "Nancy must be having a manic moment, because we’re not going

to do this."

[12:35]

We went to group therapy, and at the end of it, the lovely therapist said,

"You know, there really is a need in the community, and you ladies should

certainly take the ball and run with it."

[12:46]

At that point, everybody gave in and said, "OK," and Bebe said,

"You got me. If we’re going to do it, let’s do it." That’s how we

started the affiliate.

Dan:

[12:55] That is incredible…

[12:57]

[crosstalk]

Nancy:

[12:57] We started with the first class down where they told us it would be

like 15 or 20 people if we were lucky. We did no publicity. Again, very

reluctant for people to really know. 45 people showed up at the class. That’s

how great the need was.

Dan:

[13:15] This is incredible.

Nancy:

[13:16] It was phenomenal.

Dan:

[13:17] That’s phenomenal, and that’s great background in terms of how the

affiliate began. We talk about us being a collective, NAMI being a collective,

NAMI being a community, NAMI being a collaborator, and NAMI being a convener,

and you just illustrated that so well.

[13:37]

Linda, could you tell us more about how Bebe Moore Campbell National Minority

Mental Health Month came about, and why?

Linda:

[13:47] One of the things that Bebe was very clear on, and that was that if we

could erase the stigma of mental illness in our communities, our people would

be more reticent about getting help. They would be more ready to get help.

[14:03]

She was at my house here in Washington, D.C. Anytime she came on the East

Coast, she always stayed with me. We were up late one night because she loves

those late‑night talks. I’m trying to get some sleep, she loves the late‑night

talks.

[14:17]

We were up talking, she says, "How can we get something named behind us?

We need to get something." I said, "Just claim it. Just say it."

She said, "Just say it?" I said, "What month do you want it to

be?" [laughs] She says, "OK, let’s call it." We said July. We

said "OK."

[14:34]

She said, "You just name this?" I said, "We just name it and we

just do it." We got together, we met with the officials in Washington. I

remember it was Mayor Tony Williams that made the announcement about July being

National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month.

[14:53]

Upon her passing, I met with Congressman Albert Wynn, who was out of Maryland,

and I said, "I need your help. We need to get this month declared Mental

Health Awareness Month." We worked with Albert Wynn, who was also, by the

way, university of Pittsburgh Alum. We worked on it.

[15:17]

Mr. Hubbard and his office were so very helpful. We gave him all the wording

for it, and it passed. It passed on the first reading. I said,

"What?" [laughs] We were very excited about this.

[15:30]

I had hoped that she would be alive to hear. I just say she’s in heaven. She

must be rejoicing with us that we were able to get this month named after her

and do the work that’s necessary. We started with people in Philadelphia

helping us to do this work.

[15:45]

We looked at Pittsburgh, we looked at Baltimore, we looked at Washington, D.C.

Helping us to get the advocacy work done, because people are afraid to let

anybody know that they have any mental [inaudible] . Because it’s so looked

upon so negatively, people do not get the help that they need.

[16:06]

That was the major piece of her whole advocacy. We started working on it, and

working on it, and working on it. It is fundamentally a grassroots movement,

the same way the NAMI Urban Los Angeles got started and when it was Inglewood.

It’s a grassroots effort.

[16:26]

We know that once we put our feet to the fire, we can get things done. That’s

how we started. Of course, she passed. We wanted to keep her work alive, the

work that she had done all over the country, in terms of making people aware.

That book, "Sometimes My Mommy Gets Angry," that book was just

powerful.

[16:48]

[crosstalk]

Linda:

[16:51] A lot of young people going through this, their parents are suffering

from mental illness. They don’t know what it is. This book was a way of

explaining it. We were able to keep the momentum going even after her passing

so that her work would not be in vain.

[17:06]

That’s why we fight now so hard to keep her name within this movement. There

are those who are trying to erase her name, and so I came up with the campaign,

Erase the Stigma, Not Her Name.

Nancy:

[17:19] Amen. Thank you.

Linda:

[17:20] That’s the campaign that we’ve [laughs] been running. We’re

concentrating on the wrong thing. We should not be concentrating on her name.

We need to be concentrating on how we can erase this stigma in our communities

so our people can get the help that they need.

Dan:

[17:34] That stigma is huge.

[17:35]

[crosstalk]

Dan:

[17:36] What is the status of preserving and protecting Bebe’s name? Why is

that so important? How can individuals align as advocates to not erase Bebe’s

name from the month? My apologies for all three questions, but you’re

absolutely on it, so I wanted to go there.

Linda:

[15:32] I say to people all the time, "It’s OK, you can name it BIPOC

Month, whatever you want, but we’re going to leave this black woman’s name

alive." This movement that she started is for real. It is needed. It is

needed in the community of colors.

[18:07]

They need to see people who look like them that’s addressing this issue and is

seeking parity as it relates to treatment research in this area. We feel it is

a calling for us who are doing this. It’s a calling. It’s a labor of love, but

we must do it to save our people because mental health is real.

Nancy:

[18:29] Amen.

Linda:

[18:29] We need not to throw it under the closet. I always think about that

movie, "Soul Food", when Uncle…I forgot the uncle’s name who lived

in the house.

Nancy:

[18:38] I had one.

Linda:

[18:39] Only at the end they found out he wasn’t as crazy as they thought he

was. He came out with all that money and that TV. If you remember at the end,

he dropped the TV and all this money came running.

[18:50]

That’s what we do. We put people in the corner, we hide them because we don’t

want anybody to know, "Don’t tell anybody that Uncle Bubba is not this

talking out of his head. Let’s not telling anybody."

[19:02]

We just hide them and so we can no longer hide this illness because just like

we treat high blood pressure, diabetes, and any other illness we need to treat

mental health illness and make out people whole, make individuals whole.

[19:17]

Let’s help the families, let’s help the loved ones. All of those who are around

persons who may be impacted by mental illness, it is our duty. It is our sworn

duty to do something about it and to help this. Our task is, again, to erase

the stigma, not her name.

[19:37]

Our task is to advocate for more mental health treatment. Our task is to look

at this whole issue and say to the world, "This is real. Let us deal with

it straight up and upfront and save our people."

Dan:

[19:52] Let’s continue that conversation.

Nancy:

[19:54] Linda, thank you.

Dan:

[19:54] If I build on that, one of the ways we are continuing to build on

NAMI’s legacy across our alliance is through the development of initiatives

that encourage community conversations and safe spaces for people of color,

like sharing hope, [Spanish] , and our new BIPOP Male Mental Health Initiative.

[20:12]

What are some practical ways others can continue Bebe’s legacy of eliminating

stigma, bringing more awareness, and creating more accessible resources for

underserved communities?

Linda:

[20:24] I think as we work with our faith‑based organizations we have a

movement in Washington working with a number of the churches and faith‑based

institutions. We have to meet people where they are with this issue.

[20:37]

We have more pastors now having mental health programs within their parishes

and their churches, so that people will understand that there’s a place they

can come to get some help. We are asking our sororities and fraternities to

take this on as an issue.

[20:57]

We know since the pandemic that the mental health crisis in our children, it’s

a crisis in America right now with what’s happening with mental illness with our

children. We’re working with the American Pediatric Association right now with

getting the word out in their communities.

[21:15]

They declared, as you remember two years ago, that we are facing a mental

health crisis as it relates to children. This problem is not going away. We

can’t sweep this under the rug. We have to deal with this problem we must

address.

[21:28]

If we first start with getting people to realize that it’s OK. It is OK to talk

about this. It’s OK to get help, and we have to make those resources available

to people. I was very pleased to get the 988 number, that there’s a number that

people can now call.

[21:45]

We just got to get these states to fund this initiative, so they’re more

callers that people can call in and get help. They need to know, just like you

called 911 for help, they need to call 988 for help. That will help in some of

this police violence that we see.

[22:03]

People are mentally ill and we resort to shooting them, choking them, or choke

holds on them when it’s a mental health crisis. We have to train those who

interact with the public how to recognize the sign of mental illness, and let

them know what to do as well.

[22:21]

We have to storm the gates of heaven, if I can say and say, "Let’s get

this. We got to do this. We have to do this to save our people."

Nancy:

[22:30] Linda, thank you.

Dan:

[22:31] It’s a collective and it will take all of us. I would say to you that

as we think about NAMI moms, and we think about the legacy of NAMI starting 44

years ago by NAMI moms in Madison, Wisconsin, Bebe Moore Campbell was a NAMI

mom.

Nancy:

[22:47] Yes, she was. Absolutely.

Dan:

[22:47] We hold onto her name as a NAMI mom.

Nancy:

[22:51] Yes, absolutely.

Dan:

[22:52] That’s what we’re looking to do. We need to eliminate stigma. I want to

ask you all both this, we know the world can be a difficult place.

Nancy:

[23:01] Dan, can I just interject for one second?

Dan:

[23:03] Uh‑huh.

Nancy:

[23:04] We started in the faith‑based community, Linda. One of the first

outreaches that we did when we moved past, or whenever we moved past, teaching

family to family and the NAMI programs, but we initiated our own programs. We

reached out into the faith‑based community heavily.

[23:22]

The second thing we did was criminal justice. When we began teaching our

classes, one of the first questions I asked the families that were sitting

there, "Has any of your loved ones had involvement with the criminal

justice system?" 8 out of 10, 9 out of 10 hands would go up.

[23:41]

In our group, every single one of our loved ones had gone to jail, been

arrested. In 2005, the "LA Times" did an article on me in their

magazine section called the Go To Jail Card. What I said was, "If you were

in the throes of psychosis and walking down Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills naked,

you would have an ambulance pick you up and take you to Cedars Sinai or UCLA

Hospital."

"[24:09]

If you display the same behavior in East [inaudible] or walking down Rodeo

Drive in the Black community, you got to go to jail card." Our young

people, I don’t care whether they were from the highest to the lowest, ended up

in Twin Towers jail, which is now the first or second largest psychiatric

hospital in the country.

[24:33]

We jail people with mental illness. It is categorically wrong. No one gets well

from a jail cell. In fact, if you start out with a diagnosis, and for me, if

you spend five minutes in custody, you now have post‑traumatic stress

disorder. For every second you spend in jail, you increase the amount of time

that it takes for a person to recover.

[24:58]

We came together with a couple of the other NAMI affiliates in 2004 and we

started the first criminal justice committee. We went into the Twin Towers jail

and we conducted classes for the Sheriff’s department.

[25:12]

We took the bull by the horns and said, "OK, it’s our kids that are being

affected, and in this community, we have to do better and we will fight

back." That’s where Bebe came in. She gave all of us that energy and that

impetus to say, "We can fight back. We won’t settle for less." We

have to. Our kid’s survival is at risk.

Dan:

[25:36] Thank you very much for that. What you’ve just shared is that this is

about leadership, this is about tone, this is about execution, and this is

about being that collective.

[25:46]

I want to wrap up by asking you all both this, the world can be a difficult

place and sometimes it can be hard to hold on to hope. That’s why each week we

dedicate the last couple of minutes of our podcast to a special section called

Hold On to Hope.

[26:02]

[background music]

Dan:

[26:04] Nancy and Linda, can you tell us what helps you hold on to hope?

Nancy:

[26:09] For me, I hold on to hope by paying it forward, I talk to the

ancestors, and I try to pass it along to the next generation. We stand on

other’s shoulders. Bebe knew that only too well. We’re not the first group that

will tackle these issues. We will not be the last. When I’m really down and I’m

really low, I just listen to the voices.

[26:39]

I listen to those folks, my family, my friends, Bebe, everybody who’s passed

away, and I just ask them, "Order my steps. Put me in the right place to

make change." I pay it forward by finding other young people who are out

there in the community who want to do more. We have to invest in the next

generation.

[27:06]

I just turned 77. I’m an elder of this tribe now. For me, it’s my sacred

responsibility to pass it on. There’s a youn…