September 30, 2015

By Brendan McLean

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2015 Advocate, click here to see other articles that appeared in that issue. To receive the print edition of the Advocate, become a member today.

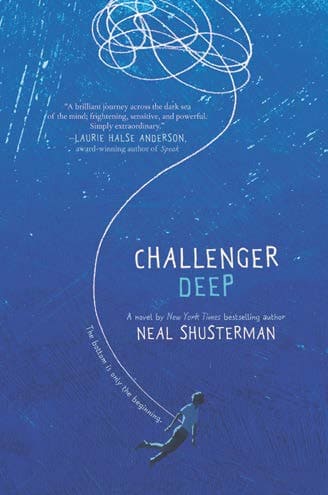

Neal Shusterman is a New York Times bestselling author of young adult fiction. With most writers, some of their own lives ultimately end up in their pages. But in Shusterman’s latest book, it may be more than usual. Challenger Deep is the story of Caden Bosch, a brilliant high school student; it’s also the story of Caden Bosch, who is on a pirate ship headed for the deepest point on earth: Challenger Deep, the southern part of the Marianas Trench.

Chapters alternate between these two realities until they ultimately begin to crash together as Caden’s world becomes more and more confused.

As Caden emerges from his fog and begins to distinguish between what is real and what is not, it becomes clear that the characters aboard the ship have real-world counterparts in the hospital that Caden has been admitted to.

Challenger Deep is based on the real-life experiences that Neal Shusterman and his family encountered when his son, Brendan, first began to experience the symptoms of a mental illness.

Working closely with his son to create this work—Brendan’s illustrations can also be found throughout the book—Shusterman has created a beautiful and heartfelt portrayal of a young man losing touch with the world around him. I was fortunate enough to be able to speak with Neal Shusterman about his book and why he decided to write a young adult novel with mental health as its central theme.

Where did the idea to first write a young adult novel with a central character affected by mental illness come from and why did you feel it was necessary to tell this story?

When my son was 16, he was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. His break left him unable to differentiate between what was real and what was in his head. He was hospitalized, and when he was in the absolute depths of his illness, he said to me, “Dad, it feels like I’m at the bottom of the ocean screaming at the top of my lungs and no one can hear me.” As an author, I’m always looking for meaningful stories—and at that moment, I knew I had to write about that feeling. Challenger Deep is the deepest place in the world—the very bottom of the Marianas Trench. I felt it was the perfect metaphor for the depths of mental illness. I couldn’t tell the story right away, though—we were in the depths with Brendan, too close to be able to look at it with any perspective. About seven years later, when he was really beginning to thrive, and had the illness under control, I asked him if I could tell a story about a teen going through what he went through. Now he’s 26, finishing up his college degree, and you’d never know he’s struggled with mental illness. There is a lot of despair when dealing with mental illness, but there is also a great deal of hope. Our story is one of hope. I wouldn’t say it’s a “happy ending,” because that’s too simplistic. Life goes on—there will be ups and downs—but right now things are good, and hopefully they’ll stay that way!

Your son’s artwork is included throughout the book. Was the writing process for this book different from others that you’ve written, and how was it working on a project with your son?

The process for writing this book was like nothing else I’ve ever written. The story takes place in two realities—Caden, the main character, is on a surreal voyage across the sea, and that’s juxtaposed against a psychotic episode in his real life. The artwork came first; it was created while Brendan was in the depths of his illness, and the images inspired a lot of the things that happen on the voyage. My editor at HarperCollins agreed that some of the artwork should be included in the book. I think it adds a powerful dimension. Also, Brendan read early drafts of the book, and helped me to shape it. His input made all the difference.

There are some passages in the book that I believe accurately convey what others going through similar experiences might feel (“I wish I’d lived in an age before technology. I would much rather everyone think I was a prophet than some poor sick kid.” “I don’t know which is more horrifying—the thought of being here for another week, or the thought that maybe the medication that I so despise might actually be working.”) How did you go about doing research to write the book, and how did you incorporate your and your son’s own experiences?

When your child has a mental illness, you become an expert—or at least an expert in your own child’s version of it. Everything came from personal experience: things our family pondered, things my son said. I spent years trying to empathize and understand what he was going through. I have a degree in sychology—but that isn’t much help when you’re in the trenches with someone you love. Nothing qualifies you for writing about mental illness like being close to someone who struggles with it—and my goal was to find a way to express what it truly feels like to be in that place. I didn’t want to tell a story “about” mental illness; I wanted to take the reader through their own episode of psychosis, to give readers a glimpse of what it’s really like.

There are also points throughout the book that bring a certain levity to some situations, such as when he asks his mother to account for inflation when she asks for a penny for his thoughts. For a topic as potentially somber and devastating as mental illness, why did you choose to include these moments?

Life, even in its most serious and somber moments, is never humorless—and those brief moments of levity help us get through the most difficult times. I remember this one time, when my son was still experiencing severe delusions. He had just gotten out of the hospital. The whole family was in

the car. Out of nowhere he heaved a heavy sigh, and said “Somewhere in the world, someone’s head just exploded.” A beat of silence, and we all just burst out laughing—even him. Stephen Hawking once said, “Life would be tragic if it weren’t funny.” I think we have to celebrate that whenever we can.

You describe the unease, but relative acceptance, at which Caden’s parents and sister come to understand his new situation. I see their story in stark contrast to Hal’s new potential stepfather. What was this experience like for you and your family, and what helped you overcome the challenges that you faced?

While Caden’s family is not our family, I modeled the dynamic after us. In so many stories about mental illness, the parents are either clueless or in denial—which does happen at times, but I feel it’s a very one-dimensional way to look at a family dynamic. Caden’s family is never in denial, but struggles with that awful sense of helplessness of not being able to “fix” the problem. On the other hand, Hal’s mother and new stepfather represent the opposite extreme. They represent the parents who distance themselves as much as possible, as a means of self-preservation. Sadly, that happens, too. You either go to the depths with your child, or you sail away and save yourself.

In the acknowledgements, you mention what a great support and resource NAMI has been for you. How did you first find NAMI, and how has it helped you and your family?

It was Brendan’s incredible psychiatrist, Dr. Robert Woods, who suggested NAMI to us, and we attended many support group meetings. NAMI made a huge difference in all of our lives. When someone in your family has a mental illness, you tend to feel isolated, and you don’t know where to turn for support. NAMI was there to show us that we weren’t alone. Brendan has been selling prints of his artwork, both at book

festivals and online — and he’s resolved to give 50% of the proceeds to NAMI as a way of giving back. Anyone interested can find his artwork on my website www.storyman.com.

Submit To The NAMI Blog

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices.

LEARN MORE